![]()

Vol. 6, No. 2, Fall 2007

![]()

|

|

|

|

Download this Article in PDF Format (Downloading commits you to accepting the copyright terms.) |

Download the Free Adobe PDF Reader if Necessary |

[page 140]

Rachel Bowditch

Temple of Tears:

Revitalizing and Inventing Ritual in the Burning Man Community in Black Rock Desert, Nevada

Underlying all rituals is an ultimate danger, lurking beneath the smallest and largest of them, the more banal and the most ambitious – the possibility that we will encounter ourselves making up our conceptions of the world, society, our very selves. We may slip in that fatal perspective of recognizing culture as our construct, arbitrary, conventional, invented by mortals.[1]

|

![]() For the purpose of this article, I focus on the ephemeral temples created between 2000 and 2004 designed by San Francisco based artist, David Best and how his temples serve as the [page 141] nexus for the formation of belief within the Burning Man community. During my fieldwork from 2001 to 2005, I observed Burning Man as both a political intervention as well as an artistic enterprise.[2] Opposing and subverting the prevailing socio-political climate, participants at Burning Man use the convergence of ritual, performance, and visual art to create an alternative world.

For the purpose of this article, I focus on the ephemeral temples created between 2000 and 2004 designed by San Francisco based artist, David Best and how his temples serve as the [page 141] nexus for the formation of belief within the Burning Man community. During my fieldwork from 2001 to 2005, I observed Burning Man as both a political intervention as well as an artistic enterprise.[2] Opposing and subverting the prevailing socio-political climate, participants at Burning Man use the convergence of ritual, performance, and visual art to create an alternative world.

![]() Black Rock City is a rich environment where new rituals and hybrid rituals drawing on traditional practices abound. Borrowing, reworking, and refashioning ritual practices, Black Rock citizens create a patchwork that forges the unique, heterogeneous identities of the participants into a temporarily harmonious community. The spectrum of reinvented ritual occurs in Black Rock City from tongue and cheek, comic rituals to serious, meaningful, efficacious ritual practice. Many participants engage in both forms of ritual practice during the week.

Black Rock City is a rich environment where new rituals and hybrid rituals drawing on traditional practices abound. Borrowing, reworking, and refashioning ritual practices, Black Rock citizens create a patchwork that forges the unique, heterogeneous identities of the participants into a temporarily harmonious community. The spectrum of reinvented ritual occurs in Black Rock City from tongue and cheek, comic rituals to serious, meaningful, efficacious ritual practice. Many participants engage in both forms of ritual practice during the week.

|

|

| |

|

![]() This inundation of spiritual information lays the groundwork for what Denny Sargent calls the "eclectic ritualist".[5] Sargent argues this phenomenon is predominantly American, and that the eclectic ritualist flips through various religious practices and sacred rituals like channels on the TV combining and weaving together a system of belief according to their spiritual wishes and needs. Throughout the week, someone wandering through Black Rock City could sample a variety of rituals becoming an eclectic ritualist.

This inundation of spiritual information lays the groundwork for what Denny Sargent calls the "eclectic ritualist".[5] Sargent argues this phenomenon is predominantly American, and that the eclectic ritualist flips through various religious practices and sacred rituals like channels on the TV combining and weaving together a system of belief according to their spiritual wishes and needs. Throughout the week, someone wandering through Black Rock City could sample a variety of rituals becoming an eclectic ritualist.

![]() These venues are not the ordinary church, mosque, or synagogue, but spirituality refracted through the lens of Burning Man: erotic, playful, and new age. One could join sunrise and sunset meditations, full moon and new moon rituals. Oracles are another popular activity, with numerous groups hosting tarot readings, rune stone making workshops, vision quests, sunrise pow-wows, guided shamanistic journeys, and talking circles. In addition to New Age practices, the "great religions" were also present on the playa. The sampler could also take a course in Judaism, participate in a Shabbat dinner, attend a Quaker meeting, attend Unitarian Universalist worship or meditate in a Zen rock garden.

These venues are not the ordinary church, mosque, or synagogue, but spirituality refracted through the lens of Burning Man: erotic, playful, and new age. One could join sunrise and sunset meditations, full moon and new moon rituals. Oracles are another popular activity, with numerous groups hosting tarot readings, rune stone making workshops, vision quests, sunrise pow-wows, guided shamanistic journeys, and talking circles. In addition to New Age practices, the "great religions" were also present on the playa. The sampler could also take a course in Judaism, participate in a Shabbat dinner, attend a Quaker meeting, attend Unitarian Universalist worship or meditate in a Zen rock garden.

|

[page 144] ![]() The ritual of the lamplighters was invented and designed by Burning Man founder, Larry Harvey, who was once a lamplighter himself. In 1993, Steve Mobia and Larry Harvey placed twenty-four lanterns on the ground leading up to the Man creating a ceremonial pathway of light. As Mobia notes, "These lamp posts give the sense of an urban space to what might otherwise be a haphazard camp. The lamps are controlled flames as opposed to the passionate flames of the Man: a balance of fires" (Newsletter 1997).

The ritual of the lamplighters was invented and designed by Burning Man founder, Larry Harvey, who was once a lamplighter himself. In 1993, Steve Mobia and Larry Harvey placed twenty-four lanterns on the ground leading up to the Man creating a ceremonial pathway of light. As Mobia notes, "These lamp posts give the sense of an urban space to what might otherwise be a haphazard camp. The lamps are controlled flames as opposed to the passionate flames of the Man: a balance of fires" (Newsletter 1997).

Rites of Passage

![]() Combining playfulness and seriousness, rites of passage are rehearsed and performed throughout Black Rock City. Crossing the threshold into the city is a rite of passage in Arnold van Gennep's sense. Using van Gennep's model, a participant separates (pre-liminal) from everyday life and surroundings and moves towards the margins, the Black Rock Desert. Upon entering the gates of Black Rock City, one crosses the threshold or limen into a new world, becoming in essence a neophyte or initiate. Van Gennep states that to pass from the profane world into the sacred, one must go through a rite of passage, going through an intermediate stage.[6] Upon crossing the threshold, clock time is transformed into "event" time. During the week in Black Rock City, many people exist in a liminal state. Participants shed their former identities and try on new ones. Sometimes these new identities stick – they are carried back into the "default"[7] world after Burning Man is over.

Combining playfulness and seriousness, rites of passage are rehearsed and performed throughout Black Rock City. Crossing the threshold into the city is a rite of passage in Arnold van Gennep's sense. Using van Gennep's model, a participant separates (pre-liminal) from everyday life and surroundings and moves towards the margins, the Black Rock Desert. Upon entering the gates of Black Rock City, one crosses the threshold or limen into a new world, becoming in essence a neophyte or initiate. Van Gennep states that to pass from the profane world into the sacred, one must go through a rite of passage, going through an intermediate stage.[6] Upon crossing the threshold, clock time is transformed into "event" time. During the week in Black Rock City, many people exist in a liminal state. Participants shed their former identities and try on new ones. Sometimes these new identities stick – they are carried back into the "default"[7] world after Burning Man is over.

![]() In Victor Turner's elaboration of van Gennep's basic idea, novices undergoing a rite of passage are stripped of their secular clothing and former identities as they pass through a symbolic gateway. They are "leveled," and their former names and selves are discarded.[8] Just so in Black Rock City where new playa names are given, quotidian clothing shed, and highly imaginative costumes – or nakedness, a costume of a different kind – are put on. During the week, the neophyte at Burning Man endures tests of survival, engages in ritualistic activity, and forms new bonds of community. Then, after this week of intense existence, the neophyte, now [page 145] changed, reintegrates (post-liminal) back into his/her community.[9] Some are transformed while others are only transported.

In Victor Turner's elaboration of van Gennep's basic idea, novices undergoing a rite of passage are stripped of their secular clothing and former identities as they pass through a symbolic gateway. They are "leveled," and their former names and selves are discarded.[8] Just so in Black Rock City where new playa names are given, quotidian clothing shed, and highly imaginative costumes – or nakedness, a costume of a different kind – are put on. During the week, the neophyte at Burning Man endures tests of survival, engages in ritualistic activity, and forms new bonds of community. Then, after this week of intense existence, the neophyte, now [page 145] changed, reintegrates (post-liminal) back into his/her community.[9] Some are transformed while others are only transported.

![]() While this might seem like a romanticized scenario, many participants experience this kind of transformation when attending Burning Man for the first time. This promise of transformation has become a highly marketable ephemeral commodity for Burning Man organizers in what could be called the experience economy. And while some experience Burning Man as one big party, many others find the experience is deep and personal, affecting real life changes. The key is that fun and seriousness go together in Black Rock City. It is not an either/or situation.

While this might seem like a romanticized scenario, many participants experience this kind of transformation when attending Burning Man for the first time. This promise of transformation has become a highly marketable ephemeral commodity for Burning Man organizers in what could be called the experience economy. And while some experience Burning Man as one big party, many others find the experience is deep and personal, affecting real life changes. The key is that fun and seriousness go together in Black Rock City. It is not an either/or situation.

|

Memory and Loss: David Best's Temples

![]() One of Burning Man's most magnificent artistic accomplishments, merging visual art and ritual on a grand scale, are Best's temples created from 2000 to 2004. Before coming to Burning Man for the first time in 1997, Best made his living in San Francisco working primarily with painting, prints, and sculpture. The Temple [page 146] marks a tremendous evolution in his work as an artist.

One of Burning Man's most magnificent artistic accomplishments, merging visual art and ritual on a grand scale, are Best's temples created from 2000 to 2004. Before coming to Burning Man for the first time in 1997, Best made his living in San Francisco working primarily with painting, prints, and sculpture. The Temple [page 146] marks a tremendous evolution in his work as an artist.

|

![]() Within five years, the temples have become an integral part of the Burning Man community providing quiet spaces of prayer, meditation, and reflection. Inside the temples, participants practice whatever beliefs they choose. Best considers his temples to be the ultimate temple where all religions and belief systems are welcomed and celebrated, challenging Durkheim's assumptions that churches and temples house only one ideology and belief system.

Within five years, the temples have become an integral part of the Burning Man community providing quiet spaces of prayer, meditation, and reflection. Inside the temples, participants practice whatever beliefs they choose. Best considers his temples to be the ultimate temple where all religions and belief systems are welcomed and celebrated, challenging Durkheim's assumptions that churches and temples house only one ideology and belief system.

The Temple of Tears (2001)

|

|

![]() The Temple of Tears fused several architectural features from around the world from Pura Besakih, Bali's largest and most important temple to Angkor Wat, yet maintains a uniquely original [page 147] shape and form. When I asked Best why he built his temples, he replied:

The Temple of Tears fused several architectural features from around the world from Pura Besakih, Bali's largest and most important temple to Angkor Wat, yet maintains a uniquely original [page 147] shape and form. When I asked Best why he built his temples, he replied:

If I am building a temple, what is this about? Is it a Buddhist temple? Is it a Baptist Church? Is it a synagogue? I thought about all of those religions and there is a stigma about not being able to be buried with the rest of the dead if you have taken your own life. You put all your life into a religion and then all of a sudden because for some reason if one of your wires isn't right they won't bury you? This temple is dedicated to suicide.[10]

This is significant because in some religions, suicide is thought to be a sin; those who commit suicide are not given equal burial rights as others.

![]() In 2001, Best estimated that he talked with at least a hundred people who had all experienced suicides either by their mothers, fathers, brothers, sons, daughters, spouses, or friends. The temple became Black Rock City's sacred center, or emphalos,[11] a powerful destination for the processing of grief within the community.

In 2001, Best estimated that he talked with at least a hundred people who had all experienced suicides either by their mothers, fathers, brothers, sons, daughters, spouses, or friends. The temple became Black Rock City's sacred center, or emphalos,[11] a powerful destination for the processing of grief within the community.

The Temple of Joy (2002) and the Temple of Honor (2003)

![]() Best was so overwhelmed by the emotion he had evoked that he told Larry Harvey, that the next year he would create the Temple of Joy. And by changing the name it still had the same power but people were able to tell jokes about their father in the hospital with chemo or tell their mother's favorite joke. They were still crying but there was a sense laughter.

Best was so overwhelmed by the emotion he had evoked that he told Larry Harvey, that the next year he would create the Temple of Joy. And by changing the name it still had the same power but people were able to tell jokes about their father in the hospital with chemo or tell their mother's favorite joke. They were still crying but there was a sense laughter.

![]() Then 9/11 happened. In 2002 the Temple of Joy was dedicated to all those who died in the World Trade Center attacks and participated in the national drama; its altars expressed grief and sorrow, while also offering a place for reflection. An American flag was placed at the entrance to the temple and a chest containing the names of those killed in the attack was set on [page 148] top of the main altar.[12] A fire fighter from New York City was invited to set the temple on fire at the end of the week. Lee Gilmore remembers that at the burning of the Temple in 2002, the silence gave way to a spontaneous performance of "New York, New York".[13]

Then 9/11 happened. In 2002 the Temple of Joy was dedicated to all those who died in the World Trade Center attacks and participated in the national drama; its altars expressed grief and sorrow, while also offering a place for reflection. An American flag was placed at the entrance to the temple and a chest containing the names of those killed in the attack was set on [page 148] top of the main altar.[12] A fire fighter from New York City was invited to set the temple on fire at the end of the week. Lee Gilmore remembers that at the burning of the Temple in 2002, the silence gave way to a spontaneous performance of "New York, New York".[13]

![]() According to Sarah Pike, the Delaware Burning Man contingent, Playa del Fuego planned their annual beach burn on a stretch of Delaware coastline a month after September 11th. Pike notes, "Several hundred gathered there, many of them from New York City, and built their own mausoleum out of remnants brought home from the Temple of Tears.[14]

According to Sarah Pike, the Delaware Burning Man contingent, Playa del Fuego planned their annual beach burn on a stretch of Delaware coastline a month after September 11th. Pike notes, "Several hundred gathered there, many of them from New York City, and built their own mausoleum out of remnants brought home from the Temple of Tears.[14]

|

The Temple of Stars (2004)

![]() A year later, in 2004, he challenged himself and his crew to build their largest and most elaborate temple yet, the Temple of Stars. The Temple of Stars, constructed out of Best's trademark lattice wood, had two levels and two side ramps that extended for an eighth of a mile on each [page 149] side. But Best noted one major flaw: he did not like that people on the second level could look down on those on the first level who were grieving.

A year later, in 2004, he challenged himself and his crew to build their largest and most elaborate temple yet, the Temple of Stars. The Temple of Stars, constructed out of Best's trademark lattice wood, had two levels and two side ramps that extended for an eighth of a mile on each [page 149] side. But Best noted one major flaw: he did not like that people on the second level could look down on those on the first level who were grieving.

|

|

![]() On Friday September 3rd, 2004, I reached the temple around 11 a.m. About a thousand people were milling around inside, on the ramps and upstairs. Upon entering the temple, I felt a somber atmosphere, hushed, with people crying, meditating, praying, consoling, and writing messages to loved ones. Someone began playing a guitar. Another person on the upper level hit a Tibetan gong that resonated throughout the temple and vibrated out into the desert. A central altar, which dominated the interior of the temple and rose up into the steeple, was covered with photographs, paintings, portraits, flags, candles, burning incense and sage, books, beads, and mementos such as:

On Friday September 3rd, 2004, I reached the temple around 11 a.m. About a thousand people were milling around inside, on the ramps and upstairs. Upon entering the temple, I felt a somber atmosphere, hushed, with people crying, meditating, praying, consoling, and writing messages to loved ones. Someone began playing a guitar. Another person on the upper level hit a Tibetan gong that resonated throughout the temple and vibrated out into the desert. A central altar, which dominated the interior of the temple and rose up into the steeple, was covered with photographs, paintings, portraits, flags, candles, burning incense and sage, books, beads, and mementos such as:

"May this burn release me from my cocaine addiction,"

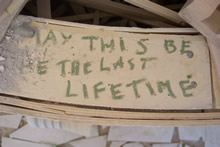

"May this be the last lifetime"

"Sorrow and pain, I thank you for your lessons,"

"My empty womb"

"Praying for a cure, a release from needle bondage"[17]

"New Orleans, my God"[18] [page 150]

|

|

|

Inscriptions on the temple surfaces

![]() The temple had become a portal through which people could communicate with the dead. According to John M. Lundquist, the temple is "associated with the realm of the dead, the underworld, the afterlife, the grave. The temple is the link between this world and the next. It has been called "an antechamber between two worlds."[19] Temples are liminal spaces for divine human encounter, for illumination, transformation and passage. Best's temples are conduits for performing what van Gennep would call "rites of separation" or funerary rites. Participants become ritual agents transforming their grief and sorrow into release.[20]

The temple had become a portal through which people could communicate with the dead. According to John M. Lundquist, the temple is "associated with the realm of the dead, the underworld, the afterlife, the grave. The temple is the link between this world and the next. It has been called "an antechamber between two worlds."[19] Temples are liminal spaces for divine human encounter, for illumination, transformation and passage. Best's temples are conduits for performing what van Gennep would call "rites of separation" or funerary rites. Participants become ritual agents transforming their grief and sorrow into release.[20]

Changing Hands: The Temple of Dreams (2005)

![]() While Best is still an active member of the Burning Man community, in 2005 he handed the responsibility of designing and building the Temple of Dreams to artist and builder Mark [page 151] Grieves.[21] Grieves designed a temple that was a light salmon pink with a main temple and several smaller temple huts evocative of a Shinto shrine. Grieves' Temple of Dreams lacked the epic scale and complexity of Best's temples. The Temple of Dreams was dedicated to the memory of Stevie,[22] a young woman who was a beloved member of the Burning Man community who was killed leaving Black Rock City in 2004 when her RV flipped over on the highway.

While Best is still an active member of the Burning Man community, in 2005 he handed the responsibility of designing and building the Temple of Dreams to artist and builder Mark [page 151] Grieves.[21] Grieves designed a temple that was a light salmon pink with a main temple and several smaller temple huts evocative of a Shinto shrine. Grieves' Temple of Dreams lacked the epic scale and complexity of Best's temples. The Temple of Dreams was dedicated to the memory of Stevie,[22] a young woman who was a beloved member of the Burning Man community who was killed leaving Black Rock City in 2004 when her RV flipped over on the highway.

|

|

The Burning of the Temple

|

|

![]() Best could be seen as a die-hard optimist, a utopian dreamer but one many people are keen to follow. As a solo artist, what Best found at Burning Man was a community. He also found that working collaboratively is deeply fulfilling and rewarding – it takes art beyond one's [page 152] self and into the community. Art becomes socially interactive and serves as a powerful gel for the community. Best's work with the temple crew, with their commitment and dedication, has extended beyond the playa and onto other venues across the U.S. After Burning Man in 2005, a group from the temple crew went down to Biloxi, Mississippi to rebuild a Buddhist temple, which had been leveled by Hurricane Katrina.[24]

Best could be seen as a die-hard optimist, a utopian dreamer but one many people are keen to follow. As a solo artist, what Best found at Burning Man was a community. He also found that working collaboratively is deeply fulfilling and rewarding – it takes art beyond one's [page 152] self and into the community. Art becomes socially interactive and serves as a powerful gel for the community. Best's work with the temple crew, with their commitment and dedication, has extended beyond the playa and onto other venues across the U.S. After Burning Man in 2005, a group from the temple crew went down to Biloxi, Mississippi to rebuild a Buddhist temple, which had been leveled by Hurricane Katrina.[24]

![]() Best's temples are perhaps the only temples in the world you can enter naked, wearing a g-string, a corset, or lingerie with knee high platform boots. No priest, mullah, rabbi, or bishop governs this Temple. It is the home to no single doctrine or belief. In her essay, "Fires of the Heart", Lee Gilmore poignantly argues that Burning Man offers an "experience of ritual without dogma".[25]

Best's temples are perhaps the only temples in the world you can enter naked, wearing a g-string, a corset, or lingerie with knee high platform boots. No priest, mullah, rabbi, or bishop governs this Temple. It is the home to no single doctrine or belief. In her essay, "Fires of the Heart", Lee Gilmore poignantly argues that Burning Man offers an "experience of ritual without dogma".[25]

![]() Like the laborious ritual of Tibetan butter sculptures or the intricate patterns and colors of Navaho sand paintings, David Best's temples are carefully constructed over months of dedication, labor, and artistic mastery. Then, like Black Rock City itself, the temple vanishes in flames and smoke, releasing the prayers and inscriptions inscribed on its surfaces.[26] From the mundane to the sublime, the spectrum of invented ritual practice occurs in a kaleidoscopic flurry throughout Black Rock City. Whether humorous or serious, Burning Man offers a fertile space for the experimentation with belief, allowing each participant to forge a unique mixture of ritual eclecticism. The efficacy of these rituals is evident in the dedication of time, resources, and energy spent in the building of Black Rock City, infusing it with life, culture, meaning, and belief.

Like the laborious ritual of Tibetan butter sculptures or the intricate patterns and colors of Navaho sand paintings, David Best's temples are carefully constructed over months of dedication, labor, and artistic mastery. Then, like Black Rock City itself, the temple vanishes in flames and smoke, releasing the prayers and inscriptions inscribed on its surfaces.[26] From the mundane to the sublime, the spectrum of invented ritual practice occurs in a kaleidoscopic flurry throughout Black Rock City. Whether humorous or serious, Burning Man offers a fertile space for the experimentation with belief, allowing each participant to forge a unique mixture of ritual eclecticism. The efficacy of these rituals is evident in the dedication of time, resources, and energy spent in the building of Black Rock City, infusing it with life, culture, meaning, and belief.

[page 153] Works Cited

Gilmore, Lee. "Fire of the Heart: Ritual, Pilgrimage, and Transformation at Burning Man." After Burn: Reflections on Burning Man. Eds. Mark Gilmore and Lee van Proyen. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005.

Grimes, Ronald L. Readings in Ritual Studies. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1996.

Moore, Sally Falk, and Barbara G. Myerhoff. Secular Ritual. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1977.

Nibley, Hugh, and Don E. Norton. Temple and Cosmos : Beyond this Ignorant Present. Vol. 12. Salt Lake City, Utah; Provo, Utah: Deseret Book Co.; Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1992.

Pike, Sarah M. "No Novenas for the Dead: Ritual Action and Communal Memory at the Temple of Tears." After Burn: Reflections on Burning Man. Eds. Lee van Proyen and Mark Gilmore. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005.

Sargent, Denny. Global Ritualism : Myth and Magic Around the World. St. Paul, Minn.: Llewellyn, 1993.

Shipwreck. "The Temple is Coming". Black Rock Gazette Wednesday August 27, 2003.

Turner, Victor Witter. The Ritual Process : Structure and Anti-Structure. Vol. 1966. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995.

van Gennep, Arnold. ""Territorial Passage and the Classification of Rites"." Readings in Ritual Studies. Ed. Ronald L. Grimes. Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1996.

van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

[page 154] List of Figures

Figure 1 The Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 2 Crimson Rose Opening Fire Ceremony 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 3 "Talk To God" 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 4 Hello Kitty Altar. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 5 The Lamplighter Procession 2001. Photograph courtesy of Stewart Harvey.

Figure 6 Couple lying in Coffin outside of "Camp Hex." Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 7 The Temple of the Mind created by David Best 2000. Photograph courtesy of Virgil Mirano.

Figure 8 The Temple of Tears created by David Best 2001. Photograph courtesy of Red James.

Figure 9 The Temple of Honor created by David Best 2003. Photograph courtesy of Steven Fritz.

Figure 10 Interior of the Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 11 Interior of the Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 12 "May this be the Last Life Time" Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 13 "New Orleans: My God" Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 14 Mementos/ Altars at Temple of Stars 2004. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 15 The Temple of Dreams created by Mark Grieves 2005. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 16 The Temple of Dreams created by Mark Grieves 2005. Photograph courtesy of John Tzelepis.

Figure 17 The burning of the Temple of Joy 2002. The Photograph courtesy of Steven Fritz.

Endnotes

- Sally Falk Moore and Barbara G. Myerhoff, Secular Ritual (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1977) 18.

- My fieldwork from 2001 to 2005 required a critical rethinking of methodological approaches towards the archive and how we document the ephemeral, especially art predicated on disappearance, that is constructed to be destroyed. I conducted over seventy-five interviews with key Burning Man personnel as well as participants, performers, and artists who play a significant role within the artistic community of Burning Man. Through interviews and detailed participant-observation, I have gained an in-depth understanding of the Burning Man organization, how it functions, how the city is created, how the population has grown and evolved, how art, performance, and ritual are integrated into the community, and how Burning Man has profoundly transformed the lives of many of its participants. Merging participant-observation, interviews, photographic, and video documentation with archival research (documents, newspaper articles, photographs, and digital archival resources) I analyze the event fusing quantitative and qualitative methods.

- The Burning Man Organization is a limited liability corporation with a board of six directors – Larry Harvey, Crimson Rose, Will Roger, Michael Michael, Marian Goodell, and Harley Dubois and a senior staff of employees. The majority of the labor is volunteer-based.

- Moore and Myerhoff 4. In Secular Ritual (1977), Sally F. Moore and Barbara G. Myerh off argue the sacred is a wider category than religion, rejecting Emile Durkheim's binary of the profane and the sacred. Secular rituals can be found in all contexts from court trails, graduations and other formal gatherings that make up the fabric of social life.

- Denny Sargent, Global Ritualism: Myth and Magic Around the World (St. Paul, Minn.: Llewellyn, 1993) 165.

- Arnold Van Gennep, The Rites of Passage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1960) 3.

- The "default world" is the term used by Burners to designate the world that exists outside of Black Rock City, also know as everyday life.

- Victor Witter Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1966) 108.

- Turner 94.

- Interview with author in Black Rock City, 2005.

- Hugh Nibley, and Don E. Norton, Temple and Cosmos: Beyond this Ignorant Present (Salt Lake City, Utah; Provo, Utah: Deseret Book Co.; Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies,1992) 15. Nibley states, "For the Egyptians and the Babylonians, the temple represented the principle of ordering the universe. It is the hierocentric point around which all things are organized. It is the omphalos "navel" around which the earth is organized. The temple is a scale model of the universe, boxed to the compass, a very important feature of every town in our contemporary civilization, as in the ancient world."

- Sarah M. Pike, "No Novenas for the Dead: Ritual Action and Communal Memory at the Temple of Tears," in After Burn: Reflections on Burning Man, ed. Mark Van Proyen and Lee Gilmore (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005) 208.

- Lee Gilmore, "Fire of the heart: Ritual, Pilgrimage, and Transformation at Burning Man," in After Burn: Reflections on Burning Man, 50.

- Pike 208.

- Interview with author, 2005.

- Shipwreck, "The Temple is Coming," Black Rock Gazette, Wednesday August 27, 2003.

- Inscriptions from the Temple of Stars are from my fieldnotes in 2004.

- "New Orleans, my god" were from my fieldnotes in 2005.

- John M. Lundquist, Temple: Meeting Place of Earth and Heaven (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993) 104.

- Arnold Van Gennep, "Territorial Passage and the Classification of Rites" in Readings in Ritual Studies., ed. Ronald L. Grimes (Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1996) 532.

- In 2006, the Temple of Hope was designed by Mark Grieve and the Temple crew. In 2007, the Temple of Forgiveness was once again designed by David Best and Tim Dawson.

- Stevie's last name is deliberately left out to protect her identity.

- Pike 211.

- In the spring of 2005, David Best and his temple crew worked on two temple projects outside of Black Rock City: the Chapel of the Day Laborer (2005) and Temple at Hayes Green (2005) San Francisco. The Chapel of the Laborer was to be located as a temporary art installation in San Rafael, a small city in Marin County just north of San Francisco. The Chapel, some 30 feet tall, was designed for a green space beside the main entrance to a market in the Canal District of San Rafael — a neighborhood that is home to many Hispanic day laborers. The Temple at Hayes Green was situated on a new green space at the intersection of Hayes and Octavia in San Francisco.

- Gilmore 45.

- In Chinese funerals, hell money and paper effigies are burnt as a symbolic offering, transferring these goods to the afterlife. The temple serves a similar function by releasing personal messages to the afterlife.

|

|

|

![]()

Rachel Bowditch is an Assistant Professor in the School of Theatre and Film at Arizona State University. She received her PhD in Performance Studies from New York University. She has presented her research nationally and internationally at conferences such as ATHE, ASTR, PSi, and the Hemispheric Institute. Her book, Burning Man: Ritual, Performance, and the Experience Economy (working title) is forthcoming (2009) as part of the Enactments Series (Seagull Press/Palgrave MacMillan). Her directing work can be seen at www.vesselproject.org.