![]()

Vol. 6, No. 2, Fall 2007

![]()

|

|

|

|

Download this Article in PDF Format (Downloading commits you to accepting the copyright terms.) |

Download the Free Adobe PDF Reader if Necessary |

[page 94]

Allie Terry

Meraviglia on Stage:

Dionysian Visual Rhetoric and Cross-Cultural Communication

at the Council of Florence

![]() In his Memoirs of the Council of Florence, Sylvester Syropoulos recorded a statement by Gregory Melissenos, the Byzantine emperor's confessor, which describes Greek feelings of alienation from Italian church decoration during the years of 1438-9:

In his Memoirs of the Council of Florence, Sylvester Syropoulos recorded a statement by Gregory Melissenos, the Byzantine emperor's confessor, which describes Greek feelings of alienation from Italian church decoration during the years of 1438-9:

When I enter a Latin church, I do not revere any of the

saints that are there because I do not recognize any of them.

At the most I may recognize Christ, but I do not revere him

either, since I do not know in what terms he is inscribed.

So I make the sign of the cross and I revere this sign that I have

made myself, and not anything that I see there.[1]

As Barbara Zeitler has discussed, Melissenos' refusal to venerate Italian images is a poignant instance of "cross-cultural interpretation," or, better, misinterpretation; the Greek church official did not recognize the visual vocabulary of the Italian churches, thus he made the bodily gesture of the cross and revered his own performative sign instead of anything else within the church.[2]

![]() If we imagine for a moment the visual setting of the primary locations for the council in Florence, not least of which was the newly domed cathedral of the city, Florentine visual culture [page 95] was on the verge of its most innovative moment since the days of Giotto. Following the lead of Donatello, Ghiberti and Brunelleschi, painters forged new paths for the visual exploration of form through the renewed interest in direct representation from nature, and approached the two-dimensional surface plane as though a window onto reality. Leon Battista Alberti's treatise on painting was released in Latin and Italian versions just a few years prior to the council; Masaccio's demonstrations of near-one-point perspective graced the walls of the papal residence in the city; Paolo Uccello's frescoed equestrian monument to Sir John Hawkwood lined the nave of the cathedral.[3] Seen through the eyes of a Byzantine worshipper, these images would have necessarily appeared foreign, since in both form and concept they are antithetical to the Byzantine notion of the image.[4]

If we imagine for a moment the visual setting of the primary locations for the council in Florence, not least of which was the newly domed cathedral of the city, Florentine visual culture [page 95] was on the verge of its most innovative moment since the days of Giotto. Following the lead of Donatello, Ghiberti and Brunelleschi, painters forged new paths for the visual exploration of form through the renewed interest in direct representation from nature, and approached the two-dimensional surface plane as though a window onto reality. Leon Battista Alberti's treatise on painting was released in Latin and Italian versions just a few years prior to the council; Masaccio's demonstrations of near-one-point perspective graced the walls of the papal residence in the city; Paolo Uccello's frescoed equestrian monument to Sir John Hawkwood lined the nave of the cathedral.[3] Seen through the eyes of a Byzantine worshipper, these images would have necessarily appeared foreign, since in both form and concept they are antithetical to the Byzantine notion of the image.[4]

![]() Given that the incident supposedly occurred during the Council of Florence, the ecumenical council designed to unite the Greek and Latin churches in the face of Ottoman invasion of the Byzantine Empire, one can also read the Byzantine official's resistance to the Florentine image as a political act. Many of the issues at stake in the debates for and against ecumenical union revolved around critical differences in the ritual traditions of the two churches across a wide-range of Christian religious contexts. To unify meant to surmount the differences in the language, script, and performance of the liturgy. As Melissino's remarks suggest, visual culture was also at stake, and, in this instance, may be understood as underscoring a national political identity, since the performance of religious worship was tied to a codified set of visual cues embedded within the architectural and decorative frame of each delegation's church.

Given that the incident supposedly occurred during the Council of Florence, the ecumenical council designed to unite the Greek and Latin churches in the face of Ottoman invasion of the Byzantine Empire, one can also read the Byzantine official's resistance to the Florentine image as a political act. Many of the issues at stake in the debates for and against ecumenical union revolved around critical differences in the ritual traditions of the two churches across a wide-range of Christian religious contexts. To unify meant to surmount the differences in the language, script, and performance of the liturgy. As Melissino's remarks suggest, visual culture was also at stake, and, in this instance, may be understood as underscoring a national political identity, since the performance of religious worship was tied to a codified set of visual cues embedded within the architectural and decorative frame of each delegation's church.

![]() Since Vasari's exaggerated praise of the new Tuscan manner of painting over the maniera greca, much scholarship has focused on the divergent qualities of Florentine images at mid-century and their Byzantine predecessors. This has encouraged the characterization of pictorial representation in the West and East as a set of dichotomies: perspective versus reverse [page 96] perspective; innovation versus tradition; ingenuity versus stagnation; and so on.[5] The privileged position given in Western art history to paintings that operate within the Albertian notion of the image—that is, images that follow Alberti's instructions for rendering three-dimensional volume and space on the two-dimensional surface plane— is in part connected to the Western notion of progress and Burckhardt's "civilizing" trend toward the individual, what Panofsky tied to the notion of a "modern" perspective.[6]

Since Vasari's exaggerated praise of the new Tuscan manner of painting over the maniera greca, much scholarship has focused on the divergent qualities of Florentine images at mid-century and their Byzantine predecessors. This has encouraged the characterization of pictorial representation in the West and East as a set of dichotomies: perspective versus reverse [page 96] perspective; innovation versus tradition; ingenuity versus stagnation; and so on.[5] The privileged position given in Western art history to paintings that operate within the Albertian notion of the image—that is, images that follow Alberti's instructions for rendering three-dimensional volume and space on the two-dimensional surface plane— is in part connected to the Western notion of progress and Burckhardt's "civilizing" trend toward the individual, what Panofsky tied to the notion of a "modern" perspective.[6]

![]() Yet, the Albertian trend was not the only mode of image-making in Florence at mid-fifteenth-century. There was an equally significant trend of painting that purposefully resisted the full realization of perspectival rendering and drew attention to the material artifice of the image as opposed to illusion. These paintings privilege an "optical" sensibility over the "tactile"; they draw attention to the material structure on which the representation has been made by rendering "space" as a flat pictorial surface.[7]

Yet, the Albertian trend was not the only mode of image-making in Florence at mid-fifteenth-century. There was an equally significant trend of painting that purposefully resisted the full realization of perspectival rendering and drew attention to the material artifice of the image as opposed to illusion. These paintings privilege an "optical" sensibility over the "tactile"; they draw attention to the material structure on which the representation has been made by rendering "space" as a flat pictorial surface.[7]

![]() Georges Didi-Huberman's analysis of the marmi finti panels in Fra Angelico's paintings has drawn attention to this purposeful incorporation of dissemblance in works of Italian art.[8] Like the polychrome marble revetments on the walls of Hagia Sophia and mimicked in the painted walls of churches in Florence, the zones of fictive marble in Angelico's paintings are "excessively material," that is, they resist illusionism and instead function to activate the mind of the viewer, pushing him beyond the visible and into the realm of contemplation.[9] The figuration in the foreground of Angelico's images is seen in dynamic tension with the material structures [page 97] of the marmi finti zones of color, a visual phenomenon that Didi-Huberman connected to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite's "inharmonious dissimilitudes."[10]

Georges Didi-Huberman's analysis of the marmi finti panels in Fra Angelico's paintings has drawn attention to this purposeful incorporation of dissemblance in works of Italian art.[8] Like the polychrome marble revetments on the walls of Hagia Sophia and mimicked in the painted walls of churches in Florence, the zones of fictive marble in Angelico's paintings are "excessively material," that is, they resist illusionism and instead function to activate the mind of the viewer, pushing him beyond the visible and into the realm of contemplation.[9] The figuration in the foreground of Angelico's images is seen in dynamic tension with the material structures [page 97] of the marmi finti zones of color, a visual phenomenon that Didi-Huberman connected to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite's "inharmonious dissimilitudes."[10]

|

![]() In this essay, I want to take this notion of the optical image as a site of cross-cultural communication a step further and connect both the materiality and effect of what I consider the "Dionysian image" to the performative representation of the sacre rappresentazioni, or sacred dramas, which flourished in Florence during the years of the Council. According to the first-hand testimony of a Russian representative at the Council, Bishop Abraham of Souzdal, the Latin imagery of the sacred dramas did not alienate the eastern delegation as did the imagery inside of the churches; rather, he saw affinities between the dramatic representation and Byzantine "holy pictures."[12] Nerida Newbigin has discussed these sacre rappresentazioni in their ability to present "the word made flesh"; that is, the dramas visualized the mysteries of the Church through the incarnation of actors on stage, and thus created a corporeal vision of the divine.[13] The fleshy realism of the actors was accompanied by realistic stage sets that were designed to present biblical events in tangible contexts.[14] Certain art historians have connected the dramas to developments in pictorial illusionism in fifteenth-century Italy, but, as I will argue here, despite the visualization of the mysteries through natural forms on stage, there was also an important element of artifice in the dramas—those cotton ball clouds that Vasari bragged about in the Lives—that functioned to disconnect the illusion of the drama by drawing attention to the materials of the theatrical stagecraft.[15] This disconnect between illusion and [page 99] materiality functioned like Dionysius' "inharmonious dissimilitude" and grounded the drama in the theological rhetoric of cross-cultural exchange during the Council of Florence.

In this essay, I want to take this notion of the optical image as a site of cross-cultural communication a step further and connect both the materiality and effect of what I consider the "Dionysian image" to the performative representation of the sacre rappresentazioni, or sacred dramas, which flourished in Florence during the years of the Council. According to the first-hand testimony of a Russian representative at the Council, Bishop Abraham of Souzdal, the Latin imagery of the sacred dramas did not alienate the eastern delegation as did the imagery inside of the churches; rather, he saw affinities between the dramatic representation and Byzantine "holy pictures."[12] Nerida Newbigin has discussed these sacre rappresentazioni in their ability to present "the word made flesh"; that is, the dramas visualized the mysteries of the Church through the incarnation of actors on stage, and thus created a corporeal vision of the divine.[13] The fleshy realism of the actors was accompanied by realistic stage sets that were designed to present biblical events in tangible contexts.[14] Certain art historians have connected the dramas to developments in pictorial illusionism in fifteenth-century Italy, but, as I will argue here, despite the visualization of the mysteries through natural forms on stage, there was also an important element of artifice in the dramas—those cotton ball clouds that Vasari bragged about in the Lives—that functioned to disconnect the illusion of the drama by drawing attention to the materials of the theatrical stagecraft.[15] This disconnect between illusion and [page 99] materiality functioned like Dionysius' "inharmonious dissimilitude" and grounded the drama in the theological rhetoric of cross-cultural exchange during the Council of Florence.

![]() The period leading up to and during the ecumenical council corresponds to a significant flourishing of theatrical religious spectacles in Florence, despite efforts to suppress or contain them by the Church itself. When the council was transferred to Florence in 1439 from Ferrara, the synod had already decreed that spectacles, dances and theatrics in churches were scandalous.[16] They were thus banned in houses of prayer under penalty of the law. Yet, at the moment in which the union of the Eastern and Western churches was imminent, Florentines still actively utilized their churches and piazze to stage elaborate sacred dramas. In fact, some of the most detailed descriptions of sacre rapresentazioni in Florence date from this period, and an investigation of their reception by the Eastern contingent of the Council allows for an analysis of their production, but, more importantly, their social and political function for the community as well.

The period leading up to and during the ecumenical council corresponds to a significant flourishing of theatrical religious spectacles in Florence, despite efforts to suppress or contain them by the Church itself. When the council was transferred to Florence in 1439 from Ferrara, the synod had already decreed that spectacles, dances and theatrics in churches were scandalous.[16] They were thus banned in houses of prayer under penalty of the law. Yet, at the moment in which the union of the Eastern and Western churches was imminent, Florentines still actively utilized their churches and piazze to stage elaborate sacred dramas. In fact, some of the most detailed descriptions of sacre rapresentazioni in Florence date from this period, and an investigation of their reception by the Eastern contingent of the Council allows for an analysis of their production, but, more importantly, their social and political function for the community as well.

![]() The most famous sacra rappresentazione presented in fifteenth-century Florence was the Ascension drama sponsored and produced by the Compagnia di Santa Maria delle Laude e di Sant'Agnese, a confraternity of singers and artists, at the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in the Oltrarno.[17] According to the testimony of the Russian bishop Abraham of Souzdal, an eastern representative at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438-9, the stage for the Ascension drama was set upon the permanent architectural barrier known as the tramezzo intersecting the [page 100] middle of the nave.[18] The stone structure was wide enough to stand on or walk across, thus clerics sometimes stood upon it to deliver their sermons. The sacred drama on the tramezzo stage, therefore, would have been recognized as assuming the function of a dramatic sermon or liturgy.

The most famous sacra rappresentazione presented in fifteenth-century Florence was the Ascension drama sponsored and produced by the Compagnia di Santa Maria delle Laude e di Sant'Agnese, a confraternity of singers and artists, at the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in the Oltrarno.[17] According to the testimony of the Russian bishop Abraham of Souzdal, an eastern representative at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438-9, the stage for the Ascension drama was set upon the permanent architectural barrier known as the tramezzo intersecting the [page 100] middle of the nave.[18] The stone structure was wide enough to stand on or walk across, thus clerics sometimes stood upon it to deliver their sermons. The sacred drama on the tramezzo stage, therefore, would have been recognized as assuming the function of a dramatic sermon or liturgy.

![]() On the left side of this stage, there was represented a stone castle, symbolic of the holy city of Jerusalem. On the right was a small hill, surrounded with red cloth, with a short set of stairs leading to it. A few meters above the hill was a wood platform of sorts, decorated with painted panels. At the top of this second platform there was an opening, covered by a blue cloth painted with the sun, moon and stars. High above the altar there was a small stone chamber veiled in red cloth, with a crown in front of it that slid from side to side throughout the entire performance.

On the left side of this stage, there was represented a stone castle, symbolic of the holy city of Jerusalem. On the right was a small hill, surrounded with red cloth, with a short set of stairs leading to it. A few meters above the hill was a wood platform of sorts, decorated with painted panels. At the top of this second platform there was an opening, covered by a blue cloth painted with the sun, moon and stars. High above the altar there was a small stone chamber veiled in red cloth, with a crown in front of it that slid from side to side throughout the entire performance.

![]() The drama began with the appearance of four young boys dressed as angels on top of the tramezzo, who led a young man representing Jesus Christ to the city of Jerusalem. Christ entered the city and brought out first two young men dressed as the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, then young actors dressed as Peter and the rest of the Apostles. Bishop Abraham described the Apostles as "barefoot and dressed as we see them painted in holy pictures: some have beards, others are beardless, just as they were in reality."[19] The entire entourage then set out for the Mount of Olives, the hill on the opposite side of the stage. Almost reaching the Mount, Peter and the other Apostles threw themselves, one by one, at the feet of Christ. They then reassembled around Christ and received gifts from him.[20]

The drama began with the appearance of four young boys dressed as angels on top of the tramezzo, who led a young man representing Jesus Christ to the city of Jerusalem. Christ entered the city and brought out first two young men dressed as the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, then young actors dressed as Peter and the rest of the Apostles. Bishop Abraham described the Apostles as "barefoot and dressed as we see them painted in holy pictures: some have beards, others are beardless, just as they were in reality."[19] The entire entourage then set out for the Mount of Olives, the hill on the opposite side of the stage. Almost reaching the Mount, Peter and the other Apostles threw themselves, one by one, at the feet of Christ. They then reassembled around Christ and received gifts from him.[20]

![]() The focal point of the feast day drama was the moment in which Christ ascended into heaven. When the appropriate moment arrived, thunder shook the church and Christ appeared on the Mount. The drapery covering the opening in the wooden platform above it was raised to [page 101] reveal a man representing God the Father suspended inside. Young boys dressed as angels surrounded the suspended figure of God while playing flutes, lyres, and bells and singing songs. There also were discs of paper that turned above the opening, where there were painted more life-sized angels. There was erected an elaborate cord and pulley system that was able to lower and raise a nuvola, or "cloud."[21] Attached to this nuvola were two boys dressed as angels with golden wings, who were lowered to receive Christ during his ascension. When the nuvola was about halfway lowered, Christ handed to great golden keys to Peter. Then, with the help of the ropes of the pulley system, he was raised into the air.

The focal point of the feast day drama was the moment in which Christ ascended into heaven. When the appropriate moment arrived, thunder shook the church and Christ appeared on the Mount. The drapery covering the opening in the wooden platform above it was raised to [page 101] reveal a man representing God the Father suspended inside. Young boys dressed as angels surrounded the suspended figure of God while playing flutes, lyres, and bells and singing songs. There also were discs of paper that turned above the opening, where there were painted more life-sized angels. There was erected an elaborate cord and pulley system that was able to lower and raise a nuvola, or "cloud."[21] Attached to this nuvola were two boys dressed as angels with golden wings, who were lowered to receive Christ during his ascension. When the nuvola was about halfway lowered, Christ handed to great golden keys to Peter. Then, with the help of the ropes of the pulley system, he was raised into the air.

![]() The Russian bishop's amazement with the drama and its technological representations is clear. Souzdal described Christ's Ascension as "a marvelous sight and without equal." He drew particular attention to the ingenuity of the pulley system to simulate the illusion that Christ was indeed raised into the air. But still, he recognized the materiality of the drama, the system behind it, and he was even more amazed because of it:

The Russian bishop's amazement with the drama and its technological representations is clear. Souzdal described Christ's Ascension as "a marvelous sight and without equal." He drew particular attention to the ingenuity of the pulley system to simulate the illusion that Christ was indeed raised into the air. But still, he recognized the materiality of the drama, the system behind it, and he was even more amazed because of it:

The ropes are set in motion by means of a very clever

pulley system, so that the person who represents Jesus

seems really to go up by himself, and he reaches a great

height without wobbling. The pulley-system is invisible.

The Holy Virgin and the Apostles, seeing him depart, shed

tears. When he approaches the nuvola, this envelopes him

head to foot, the two Angels bow before him on the left and

the right, and in the same instant the nuvola is lit by a multitude

of lights which shed their splendor everywhere. But Jesus goes

higher and higher, accompanied by the two Angels, and soon

he steps out to God the Father, the music ceases and it grows

[page 102] dark. Then the Virgin and the Apostles look up to the chamber

above the altar: the curtain is drawn back from the place which

represents upper Heaven, and there is light again.[22]

The Bishop's description of the flawless craftwork behind Christ's Ascension—so flawless that it even accounted for and prevented any wobbling of Christ as he ascended higher and higher into the rafters— indicates that the audience witnessing the dramatic action was acutely aware of the materials of the representations, yet was still amazed by the intense levels of illusionism achieved by the manipulation of the artist.

![]() Abraham of Souzdal's opinion about the "marvelous sights" of the Florentine religious theater was not universal among his contemporaries. Already by the late 1420s, many religious figures considered the staging of the sacred mysteries to push ideological boundaries of representation. Certain Greeks, for example, were appalled by the Latin practice of directly representing the divine through impersonation on the stage. The archbishop of Thessaloniki, Symeon wrote:

Abraham of Souzdal's opinion about the "marvelous sights" of the Florentine religious theater was not universal among his contemporaries. Already by the late 1420s, many religious figures considered the staging of the sacred mysteries to push ideological boundaries of representation. Certain Greeks, for example, were appalled by the Latin practice of directly representing the divine through impersonation on the stage. The archbishop of Thessaloniki, Symeon wrote:

[The Latins] make plays in spite of the holy laws…by putting

there human actors, in spite of what is accepted…And to

depict the Mother of God by a man or a strumpet…this is

very wrong. And with alien hair and clothing to depict the

shapes of saints, and to decorate in spite of the pious thing,

it is not allowed by the Fathers. And simply to show the holy

just as on stage and in drama is not pious nor allowed, neither

is it worthy of Christians. [23]

For Symeon, the dramatic representation of the sacred narratives was a means of offering false idols to an audience. The theologian based his objections on the Orthodox requirements for [page 103] "proper" religious images: the representation must use appropriate materials and the image must be based on the divine prototype. Therefore, the young boy dressed as Mary or God the Father was not only pretending to represent a saintly figure despite his gender and age, but he did so knowing that he was falsely representing a divine personage in the human, and therefore stained, material of the flesh.

![]() But for Bishop Souzdal, the actors were not performing in an improper manner; rather, they performed iconically. He described them as "barefoot and dressed as we see them painted in holy pictures." It was the flesh and costumes of the actors that connected them to the holy personages in iconic images, yet, the Orthodox position clearly depended on a direct correspondence to the divine prototype for images.

But for Bishop Souzdal, the actors were not performing in an improper manner; rather, they performed iconically. He described them as "barefoot and dressed as we see them painted in holy pictures." It was the flesh and costumes of the actors that connected them to the holy personages in iconic images, yet, the Orthodox position clearly depended on a direct correspondence to the divine prototype for images.

![]() The flesh of the actors may have been precisely the reason for the continual success of these sacred dramas in Italy throughout the rest of the Quattrocento, and may have been the impetus toward the theatrical pursuits of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries up until Bernini.[24] The incarnation of the divine teachings on stage may be in part connected to an increasing desire for a more "tangible" God after the Black Death.[25] The desire for praesentia in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, what Peter Brown considers the "yearning for proximity," was evidenced through the popularity of images and objects that emphasized the physicality of Christ and the saints.[26] New iconographical subjects, such as the Doubting St. Thomas in which the validity of faith is tested both through seeing and touching Christ's wounds, gained in popularity, as did the mania for relics. Similarly, Boccaccio's Fra Cipolla tale in the Decameron—a parody of his contemporaries' desire for proof of the physical existence of [page 104] the holy—serves as a testament to the preoccupation with the ways in which belief was shaped and manipulated in the early Renaissance.[27]

The flesh of the actors may have been precisely the reason for the continual success of these sacred dramas in Italy throughout the rest of the Quattrocento, and may have been the impetus toward the theatrical pursuits of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries up until Bernini.[24] The incarnation of the divine teachings on stage may be in part connected to an increasing desire for a more "tangible" God after the Black Death.[25] The desire for praesentia in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, what Peter Brown considers the "yearning for proximity," was evidenced through the popularity of images and objects that emphasized the physicality of Christ and the saints.[26] New iconographical subjects, such as the Doubting St. Thomas in which the validity of faith is tested both through seeing and touching Christ's wounds, gained in popularity, as did the mania for relics. Similarly, Boccaccio's Fra Cipolla tale in the Decameron—a parody of his contemporaries' desire for proof of the physical existence of [page 104] the holy—serves as a testament to the preoccupation with the ways in which belief was shaped and manipulated in the early Renaissance.[27]

![]() The origins of sacred drama may be directly tied to this yearning by the faithful for a more tangible connection to the holy. As early as the ninth century, theatrical elements were introduced into the liturgy in an effort to overcome the alienation of the Latin mass and to facilitate communication between the clergy and the congregation.[28] Over time independent dramatic presentations of Biblical or festal narratives were developed by the clergy to further explicate the narratives for the congregation and to facilitate individual and communal identification with the scenes represented.[29]

The origins of sacred drama may be directly tied to this yearning by the faithful for a more tangible connection to the holy. As early as the ninth century, theatrical elements were introduced into the liturgy in an effort to overcome the alienation of the Latin mass and to facilitate communication between the clergy and the congregation.[28] Over time independent dramatic presentations of Biblical or festal narratives were developed by the clergy to further explicate the narratives for the congregation and to facilitate individual and communal identification with the scenes represented.[29]

Modern ritual historians, such as Roy A. Rappaport, are clear to distinguish between the forms of the liturgy and the theater as ritual and drama, respectively:

Ritual and drama, at least in their popular forms, are best

distinguished. For one thing, dramas have audiences, rituals

have congregations. An audience watches a drama, a congregation

participates in a ritual...those who act in drama are 'only acting,'

which is precisely to say that they are not acting in earnest...Ritual

in contrast, is in earnest, even when it is playful, entertaining,

[page 105] blasphemous, humorous, or ludicrous.[30]

However, this theoretical distinction between ritual and drama became blurred with sacred dramas because the audience and the congregation were one and the same. The ephemeral stage sets, costumes, and gestures of the actors on the stage were not merely vehicles for spectacle. Rather, they were combined with the element of the eternal, the Holy Scripture, thereby transforming the dramatic action into the means by which the congregation of believers came to identify with scripture or historical time.

![]() In one of the earliest documented reactions to sacred drama in Italy, Angela of Foligno described how the dramatization of the sacred mysteries transformed her understanding of the divine into a personalized vision. She wrote,

In one of the earliest documented reactions to sacred drama in Italy, Angela of Foligno described how the dramatization of the sacred mysteries transformed her understanding of the divine into a personalized vision. She wrote,

when the passion of Christ was presented on the Piazza

Santa Maria, the moment when it seemed to me one should

weep was transformed for me into a very joyful one, and I

was miraculously drawn into a state of such delight that when

I began to feel the impact of this indescribable experience of

God, I lost the power of speech and fell flat on the ground;

[...] the use of my members was gone. It seemed to me that I had

entered at that moment within the side of Christ. All sadness

was gone and my joy was so great that nothing can be said about it.[31]

Angela's mystical identification with the body of Christ here was in part inspired by the visual cues of the narrative drama of the Passion. By introducing a human element into Scriptural narratives, sacred dramas incorporated praesentia into the distant and not easily graspable [page 106] Biblical past. Through the simulated presence of the divine, audiences of believers were encouraged to identify with that past, albeit through counterfeit means.[32]

![]() The patrons and actors of these sacred dramas were part of the same congregation of the faithful as was the audience, therefore further blurring the boundaries between drama and ritual. The number of sacred dramas produced in Florence dramatically increased in the fifteenth century, almost in direct correspondence with the rise in lay confraternities dedicated to saints and religious mysteries in churches throughout the city.[33] One of the primary responsibilities of a confraternal organization was to sponsor and produce for its dedicatee appropriate liturgical and festal celebrations, which developed into the elaborate sacred dramas. The hands-on participation of the laity in the visualization of the mysteries of the church was a concrete way of their finding and shaping a more tangible religion.

The patrons and actors of these sacred dramas were part of the same congregation of the faithful as was the audience, therefore further blurring the boundaries between drama and ritual. The number of sacred dramas produced in Florence dramatically increased in the fifteenth century, almost in direct correspondence with the rise in lay confraternities dedicated to saints and religious mysteries in churches throughout the city.[33] One of the primary responsibilities of a confraternal organization was to sponsor and produce for its dedicatee appropriate liturgical and festal celebrations, which developed into the elaborate sacred dramas. The hands-on participation of the laity in the visualization of the mysteries of the church was a concrete way of their finding and shaping a more tangible religion.

![]() The artists selected to carry out this visualization of the laity had the responsibility of creating dramatic representations that would convey Scriptural information while also creating an environment for the divine. Whereas the artist had particular tools at his disposal for representing the divine in the painted image, such as the dramatic and often fantastic manipulation of light and color, visualizing the mysteries on stage presented difficulties of time and space. The sheer technological obstacles that presented themselves, such as the logistics of raising a man into the air or coordinating the simultaneous lighting of hundreds of candles at once, were part of the problem, drawing attention to the difficulties of staging a "miracle." So, too, was the coarseness of the materials available for the scenery and stage props.[34] Yet, again, the humanity of the drama—its material incongruities with the divine—may have helped a churchgoer of the fifteenth-century to better identify with the sacred histories as something cognitively attainable. Even though Bishop Abraham knew that the man representing God the [page 107] Father was a Florentine, and that the Ascension of Christ was feigned through the use of a pulley system, he still felt awe at the sight of the materialization of the divine mystery.

The artists selected to carry out this visualization of the laity had the responsibility of creating dramatic representations that would convey Scriptural information while also creating an environment for the divine. Whereas the artist had particular tools at his disposal for representing the divine in the painted image, such as the dramatic and often fantastic manipulation of light and color, visualizing the mysteries on stage presented difficulties of time and space. The sheer technological obstacles that presented themselves, such as the logistics of raising a man into the air or coordinating the simultaneous lighting of hundreds of candles at once, were part of the problem, drawing attention to the difficulties of staging a "miracle." So, too, was the coarseness of the materials available for the scenery and stage props.[34] Yet, again, the humanity of the drama—its material incongruities with the divine—may have helped a churchgoer of the fifteenth-century to better identify with the sacred histories as something cognitively attainable. Even though Bishop Abraham knew that the man representing God the [page 107] Father was a Florentine, and that the Ascension of Christ was feigned through the use of a pulley system, he still felt awe at the sight of the materialization of the divine mystery.

![]() This sense of awe, wonder, or amazement—what one may plausibly consider a prototype of the later Baroque conception of the term meraviglia—had in large part to do with the ability of the artist to visually represent the divine in a way that both encouraged the viewer to personally identify with the saint or scene represented and to feel at the same time somewhat distanced from it, in recognition of the intensely spiritual nature of the depiction.[35] The term meraviglia is recognized as a defining concept for Baroque art; however, I believe that one may meaningfully draw upon the term to discuss the optical sensibility of images like Angelico's frescoes at San Marco and the performative practices of the sacred dramas in Florence. Both the aims and the means of this art may be tied to meraviglia, in the sense of the term used for artists of the Baroque period. That is, the aim was to literally move the viewer by means of the persuasiveness of the craft, and the primary means by which this persuasive effect was achieved was through the surface.

This sense of awe, wonder, or amazement—what one may plausibly consider a prototype of the later Baroque conception of the term meraviglia—had in large part to do with the ability of the artist to visually represent the divine in a way that both encouraged the viewer to personally identify with the saint or scene represented and to feel at the same time somewhat distanced from it, in recognition of the intensely spiritual nature of the depiction.[35] The term meraviglia is recognized as a defining concept for Baroque art; however, I believe that one may meaningfully draw upon the term to discuss the optical sensibility of images like Angelico's frescoes at San Marco and the performative practices of the sacred dramas in Florence. Both the aims and the means of this art may be tied to meraviglia, in the sense of the term used for artists of the Baroque period. That is, the aim was to literally move the viewer by means of the persuasiveness of the craft, and the primary means by which this persuasive effect was achieved was through the surface.

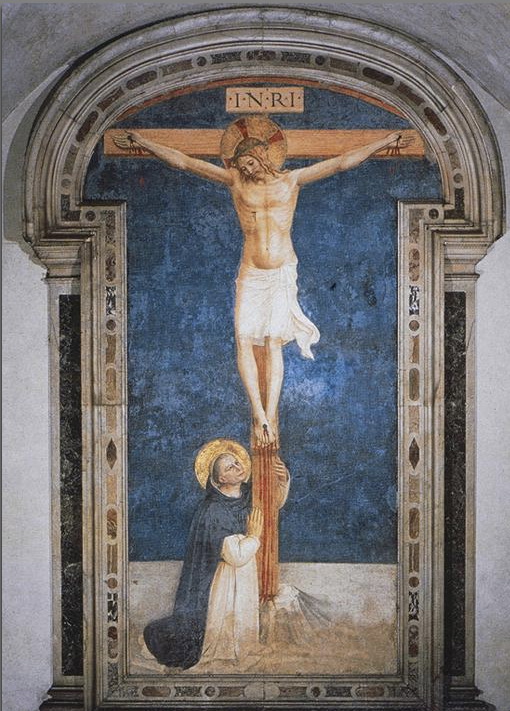

![]() The spatial constructions of Fra Angelico's frescoes at San Marco are representative of one style of painting that combated the urge toward a totalistic conception of perspective in the early Renaissance. Angelico demonstrated his ability to construct correct perspectival compositions at points throughout his career, but, in the Medici commission at San Marco, he challenged the mimetic trend of the early Renaissance by purposefully suppressing the development of the middle and background fields. His simultaneous development of three-dimensional human form in the foreground and relegation of the background to a two-dimensional plane creates a dynamic tension between illusionism and iconic representation. The images create the illusion that the persons represented are faithful imitations of nature yet, at the same time, they draw attention to the artificial construct of the figural placement and [page 108] isolate them as iconic.[36] This style of painting, in which barriers to pure imitation were purposefully retained, enabled him to continue to communicate to the viewer in a mode of meraviglia that perspectival images no longer could.[37]

The spatial constructions of Fra Angelico's frescoes at San Marco are representative of one style of painting that combated the urge toward a totalistic conception of perspective in the early Renaissance. Angelico demonstrated his ability to construct correct perspectival compositions at points throughout his career, but, in the Medici commission at San Marco, he challenged the mimetic trend of the early Renaissance by purposefully suppressing the development of the middle and background fields. His simultaneous development of three-dimensional human form in the foreground and relegation of the background to a two-dimensional plane creates a dynamic tension between illusionism and iconic representation. The images create the illusion that the persons represented are faithful imitations of nature yet, at the same time, they draw attention to the artificial construct of the figural placement and [page 108] isolate them as iconic.[36] This style of painting, in which barriers to pure imitation were purposefully retained, enabled him to continue to communicate to the viewer in a mode of meraviglia that perspectival images no longer could.[37]

![]() Whereas the Albertian image could not speak to the Greek delegation—as Melissonos' comments revealed at the beginning of this essay—we can look to the response to sacred drama in the city during the years of the Council to try to understand what kind of aesthetic would communicate across Latin and Greek cultures. It appears that the sacred drama operated within a particular Dionysian rhetoric in which natural forms were encouraged but then purposefully obscured. Like the solid zones of undifferentiated colors in Fra Angelico's paintings at San Marco for the humanist audience, which served to block the illusionism of the picture, the sacred dramas exposed their mechanical artifice and thus ruptured the illusionistic visualization of a miracle on stage. The blending of natural and abstract forms in the sacred dramas functioned to move beyond the material of the stage and to point indexically to the true object of veneration, the divine prototype, thus presenting a visual language that communicated across the East-West divide at mid-century in Italy.

Whereas the Albertian image could not speak to the Greek delegation—as Melissonos' comments revealed at the beginning of this essay—we can look to the response to sacred drama in the city during the years of the Council to try to understand what kind of aesthetic would communicate across Latin and Greek cultures. It appears that the sacred drama operated within a particular Dionysian rhetoric in which natural forms were encouraged but then purposefully obscured. Like the solid zones of undifferentiated colors in Fra Angelico's paintings at San Marco for the humanist audience, which served to block the illusionism of the picture, the sacred dramas exposed their mechanical artifice and thus ruptured the illusionistic visualization of a miracle on stage. The blending of natural and abstract forms in the sacred dramas functioned to move beyond the material of the stage and to point indexically to the true object of veneration, the divine prototype, thus presenting a visual language that communicated across the East-West divide at mid-century in Italy.

[page 109] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1. Fra Angelico, St. Dominic with the Crucifix, Cloister of Sant'Antonino, San Marco, Florence (photo: author, with permission from the Museo di San Marco)

Endnotes

- S. Syropoulos, Les Mémoires du grand ecclésiarque de l'Église de Constantinople Sylvestre Syropoulos sur le Concile de Florence (1438-1439). Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1971.

- Barbara Zeitler, "Cross-Cultural Interpretations of Imagery in the Middle Ages," Art Bulletin 76 (Dec 1994): 680-694. As noted by Zeitler, Syropoulos misrepresented the particular political interests of Gregory Melissenos through this description of his rejection of Latin imagery and the portrayal of Melissenos as anti-unionist. Joseph Gill has demonstrated that Melissenos was, in fact, pro-unionist, thus the incident described in the Memoirs speaks more to the political slant of Syropoulos than the emperor's confessor; The Council of Florence . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959.

- Santa Maria Novella was the site of the Papal entourage, while the Duomo was used for important sessions, such as the culminating session of Union between the churches.

- The Albertian, or one-point-perspective, painting is conceived of and executed as though a window onto nature; L.B. Alberti, Della Pittura. Florence: Sansoni, 1950. Instead, the Byzantine icon employs reverse perspective to act as a window to the divine prototype. On the notion of "reverse perspective," see especially Pavel Florensky, La prospettiva rovesciata e altri scritti. Rome: Casa del libro, 1983.

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects. London: David Campbell Publishers, 1996. Note particularly Vasari's categorization of such Byzantine monuments as San Vitale in Ravenna as "large and magnificent, but of the rudest architecture," and Greek mosaics as "elementary outlines on a ground of color…works that have more of the monstrous in their lineaments than of likeness to whatsoever they represent"; vol. 1, pp. 40; 46.

- Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy. 8th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1921; Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

- "Tactile," or plastic, forms are the product of an Albertian approach, as opposed to the "optical," or flat, sensibility that has been seen as characteristic of medieval forms. For a provocative account of the optical sensibilities of modern art seen in relation to the formal elements of Byzantine art, see Clement Greenberg, "Byzantine Parallels (1958)," Art & Culture: Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, 1961: 167-170.

- Georges Didi-Huberman, Fra Angelico: Dissemblance & Figuration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Ibid., 4.

- Pseudo Dionysius the Aeropagite, Mystical Theology and the Celestial Hierarchies. Letchworth, Herts., England: Garden City Press, 1965: 25.

- Allie Terry, "Politics on the Cloister Walls: Fra Angelico and His Humanist Observers at San Marco," Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, 2005.

- For Souzdal's testimony, see Alessandro D'Ancona, Origini del Teatro Italiano. Torino, E. Loescher, 1891: Vol. I., 251-3. D'Ancona translated Wesselofsky's German translation from the Russian. For a recent English translation of many of the primary sources describing the sacred dramas in Florence, see Nerida Newbigin, Feste D'Oltrarno: Plays in Churches in Fifteenth-Century Florence. 2 vol. Florence: Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento, Studi e Testi, 1996. Souzdal had also witnessed the Annunciation sacred drama in the same year in San Felice in Piazza in Florence. Brunelleschi's technological innovations for the Annunciation play are described by Vasari in his biography of the architect.

- Nerida Newbigin, "The Word Made Flesh: The Rappresentazioni of Mysteries and Miracles in Fifteenth-Century Florence," Christianity and the Renaissance: Image and Religious Imagination in the Quattrocento. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990.

- Cesare Molinari has commented that the effectiveness of the dramas to form a personal connection with their audiences is in large part related to the amount of realism of the sets; Theater Through the Ages New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975: 108. The introduction of human actors into the narrative of the Bible is an obvious leap toward that realism.

- Vasari's description of Brunelleschi's clouds called attention to their material: "beams…covered with cotton wool." Lives, I, 166-8. See also Cyrilla Barr, "Music and spectacle in confraternity drama of fifteenth-century Florence: the reconstruction of a theatrical event." Christianity and the Renaissance: image and religious imagination in the Quattrocento. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990: 376-404. The drum of the dome and fresco of the Portinari Chapel in S. Eustorgio in Milan, 1462-1468, has been connected to Brunelleschian performances; see V.O. Fischel, "Eine Florentiner Theateraufführung in der Renaissance," Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst 31 (1920): 11-20. See also T. Verdon, "Donatello and Theatre: Stage Spaces and Projected Space in the San Lorenzo Pulpits," Artibus et Historiae 14 (1986): 40ff.

- "Concilium Basileense-Ferrariense-Florentinum-Romanum—1431-1445," Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils. Vol. 1. Edited by Norman P. Tanner, S.J. London: Sheed & Ward, 1990: 455-591.

- It was only appropriate that the Ascension drama in Florence was affiliated with a group of laudesi, since the tradition for the sacred action of the Ascension stemmed back at least to the eleventh century with the performance of the "Quem queritis" liturgical chant, performed by two alternating groups of singers. For an early example of the lauda drammatica for the Ascension in Perugia, see Vincenzo de Bartholomaeis, Laude Drammatiche e Rappresentazioni Sacre. Florence: Felice Le Monnier, 1943: 275-283. The confraternity also featured prominent early Renaissance artistsincluding Masolino, Bicci di Lorenzo, and Filippo Lippi. The Compagnia's relationship to the artistic scene in Florence is important. Due to the complexities of the costumes, scenery, and props for the Ascension drama, the Compagnia constantly employed a team of architects and artists.

- Souzdal describes it as a stone tramezzo set up on columns; "un tramezzo di pietra lungo 140 piedi, eretto su colonne alte 28 piedi," Il Luogo Teatrale a Firenze. Florence: Electra Editrice, 1975:61.

- "Gli apostolic vanno a piè nudi, e quail si veggono nelle santi immagini: alcuni barbuti, altri no, come erano realmente," Il Luogo Teatrale, 61. This reference has poignant associations with what Sixten Ringbom calls the "iconic" portrait, From Icon to Narrative: the rise of the dramatic Close-Up in Fifteenth-Century Devotional Painting. Doornspijk, The Netherlands : Davaco, 1984. For a discussion of Ringbom's thesis in relation to sacred dramas, see Milla Riggio, "Wisdom Enthroned: Iconic Stage Portraits," Drama in the Middle Ages, ed. Clifford Davidson and John H. Stroupe. New York: AMS Press, 1991: 249-279.

- One can imagine how the arrangement of the actor-Apostles on the tramezzo would have echoed Masaccio's Tribute Money in the Brancacci chapel on the right.

- For examples of reconstructions of Brunelleschi's machinery for sacred drama, see V. Mariani, "Fantasia sceneografia," Vita artistica I (1926): 19-20; V. Mariani, Storia della scenografia italiana, Florence, 1930, pl. XI; O. K. Larson, "Vasari's descriptions of Stage Machinery," Educational Theatre Journal 9 (1957): 287-299; C. Molinari, Spettacoli fiorentini del Quattrocento. Venice, 1961: 40; and A.R. Blumenthal, "A Newly Identified Drawing of Brunelleschi's Stage Machinery," Marsyas 13 (1966-1967): 20-31. The drum of the dome and fresco of the Portinari Chapel in S. Eustorgio in Milan, 1462-1468, has been connected to Brunelleschian performances; see V.O. Fischel, "Eine Florentiner Theateraufführung in der Renaissance," Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst 31 (1920): 11-20. See also T. Verdon, "Donatello and Theatre: Stage Spaces and Projected Space in the San Lorenzo Pulpits," Artibus et Historiae 14 (1986): 40ff.

- This translation by N. Newbigin, Feste, 62-3.

- Symeon of Thessaloniki, excerpts from chapter 23 of Contra Haeresies. My gratitude goes to the late Angela Volan for this translation, made from J. P. Migne, Patrologia Graeca, Paris 1857-1866, vol. 155, pp. 112-117. Symeon died in the 1420s, therefore he was not in attendance at the Council of Florence.

- The staging of sacred dramas continued throughout most of the fifteenth century, persisting despite the physical damage to the churches that housed the dramas. For instance, the weight of devices used to lower and raise human actors from the stage caused the roof of the Carmine to cave in; Vasari, "Life of Brunelleschi," Lives,166. The church of Santo Spirito burned to the ground when a stage hand forgot to blow out the lanterns that illuminated the Pentecost play. The plays were temporarily halted by the religious reformists at the end of the century, led by the Dominican Girolamo Savonarola.

- For a comprehensive exploration of Italian cultural production after the mid-fourteenth century, see Millard Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951. For an investigation of "incarnational thinking" in the middle ages, see Gerhart Ladner, "Ad Imaginem Dei: The Image of Man in Medieval Art," "Wimmer Lecture, 1962" reprinted in ed. W. E. Kleinbauer, Modern Perspectives in Western Art History. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1989: 432-461.

- P. Brown, The Cult of the Saints: its rise and function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Giovanni Boccaccio, "Fra Cipolla," Decameron VI: 10.

- The early Christian church rejected drama as a mode of expression because of the sensual connotations of "theater" as developed by Classical culture. Christians were forbidden to attend the theater, and converted actors were forced to give up their professions; see G. Crosse, The Religious Drama. London: A.R. Mowbray &Co, 1913: 3. Although Saint Augustine wrote that theater promoted paganism, gradually the church incorporated dramatic elements into the liturgy as instructional tools. Christian teachers used the dialogue form for instruction (i.e. personified virtues and vices, conversation between Christ and his disciples, etc.) because it captivated the attention of the audience. Gradually more explicit performative actions were introduced to the liturgy. For example, during the tenth century, the host was elevated only during the Paschal period for dramatic effect. By the thirteenth century, the elevation of the host was part of the normal liturgy. For an example of how the production of art was transformed by the introduction of dramatic action into the liturgy, see H. W. van Os' "The Earliest Altarpieces in Siena Cathedral." The liturgy itself may be seen as a drama, as it recreates the sacrifice of Christ during the Last Supper and is a symbolic representation of the Atoning Sacrifice. On this point, as well as for a general survey of the origins of liturgical theater arts, see A. Rouet, Liturgy and the Arts. Collegeville, MN: Order of St. Benedict, 1997: esp. 44-5. For more on the theatrical and musical developments of the liturgy, see J. Harris, Medieval Theater in Context. London and New York: Routledge, 1992: esp. Chapter 3.

- The clergy assumed the first roles in sacred representation, which were then taken over by the laity. For early accounts of Ascension plays in Italy and the northern countries, see Karl Young, The Drama of the Medieval Church. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933: 483-9.

- R.A. Rappaport, "The Obvious Aspects of Ritual," reprinted in Readings in Ritual Studies, ed. Ronald L. Grimes. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1996: 429.

- Angela of Foligno, Memorial, from Complete Works, translated by Paul Lachance. New York: Paulist Press, 1993: 175-176. I would like to thank Annika Fisher for the reference.

- As cited above, Nerida Newbigin explored connections between the sacred theaters of the fifteenth century and the Incarnation of Christ; "The Word Made Flesh." Cesare Molinari has commented that the effectiveness of the dramas to form a personal connection with their audiences is in large part related to the amount of realism of the sets; Theater Through the Ages. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975: 108. The introduction of human actors into the narrative of the Bible is an obvious leap toward that realism.

- Barbara Wisch and Diane Cole Ahl, "Introduction," Confraternities and the Visual Arts in Renaissance Italy: Ritual, Spectacle, Image. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 1.

- Vasari's description of Brunelleschi's clouds called attention to their material: "beams…covered with cotton wool." Lives, I, 166-8. See also Cyrilla Barr, "Music and Spectacle," esp. 380-7.

- Art historians may take offense of my use of the Baroque concept of meraviglia to discuss Quattrocento painting. Wölfflin's 'classic and baroque' dichotomy, though insightfully revised during the last century, remains relatively true; see Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art. Trans. M. D. Hottinger. New York: Dover Publications, 1950. However, this dichotomy stands in the way of our theoretical conception of the theatrical nature of art created over a century before the Baroque period. I draw on the term here to describe particular compositional and stylistic aspects of the San Marco frescoes, as well as the role of the spectator before the work of art.

- By "iconic," I here refer to Sixten Ringbom's use of the term as a sacred portrait that is intended to stimulate devotion; From Icon to Narrative, esp. 5-39.

- This is not to assert that the perspectival grid failed to communicate any form of wonder or amazement. To say that would be to nullify the artistic pursuits and innovations of Paolo Uccello, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and the innumerous artists fascinated by the technical vistas of Alberti's window. Nor is it to claim that the viewer failed to feel a special spatial and cognitive relationship with perspectival representations. Rather, it is to point to the lack of self-conscious cues given by the artist interested in strict mimesis that would draw attention to the image's representation, materiality or particular vantage point as feigned. The purely imitative function of art has certain earth-bound repercussions, which, as Raphael, Michelangelo, Pontormo and others in the sixteenth century would recognize, held certain limitations in the representation of the divine. Raphael's consistent compositional division between earthly vision and divine vision, represented by two separate perspectival systems and often a horizontal linear division, may be said to represent a larger trend in early Cinquecento art in which spatial illusionism was at odds with spiritual representation. This tension may also be seen in the later works of Michelangelo and the paintings of Pontormo, in which the perspectival system was discarded in favor of a more spiritual vision. See Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, 1997; and Ingrid Rowland, The Culture of the High Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. It is worth mentioning in this context that in Michelangelo's Last Judgment painted for the Sistine Chapel, considered to be a dramatic collapse of comprehensive space, he uses as a model one of the monumental figures from the San Marco Chapter Room Crucifixion!

|

|

|

![]()

Allie Terry is an Assistant Professor of Italian Renaissance Art History at Bowling Green State University. Her research focuses on the audience reception and patronage of Italian Renaissance art and performance, and approaches Renaissance art and architecture through the framework of ritual theory and practice.