|

Creativity

What is atmosphere

or mood?

What is the

emotional affect of the product on the audience? How does it make

the audience feel?

In what way does the product tap into cultural

myths, symbols, or archetypes?

How does the

product offer enlightenment or meaning?

How does

the product artistically tie to the rest of the production?

In What Way Does the Product

Tap into Cultural Myths, Symbols, or Archetypes?

One

of the more effective ways to generate emotion in an audience

member is by tying the product to myths, symbols, or archetypes.

In his A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature,

Wilfred L. Guerin explains the mythological and archetypal approaches

when analyzing literature. In this essay, I will offer excerpts

of Guerin's writing (1) and then attempt to relate his writings

to theatre. One

of the more effective ways to generate emotion in an audience

member is by tying the product to myths, symbols, or archetypes.

In his A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature,

Wilfred L. Guerin explains the mythological and archetypal approaches

when analyzing literature. In this essay, I will offer excerpts

of Guerin's writing (1) and then attempt to relate his writings

to theatre.

The

relationship between myth, symbol, or archetype and mise-en-scène

has to do with a common response not only to a common experience,

but to the artistic representation of that same common experience.

The bottom line is that on a very substantive and deep level,

we all respond to common experiences because we are all human

beings. And when a common experience is represented in the theatre,

we respond similarly to the experience, even when the common experience

is not real but representation or symbol. In The Masks of God:Primitive

Mythology, Joseph Campbell tells of the phenomenon that newborn

chicks will see a hawk fly overhead and run for cover. The chicks

do not respond the same way when they see other birds. But not

only that, a wooden image of a hawk drawn overhead on a wire will

elicit the same response. The wooden hawk run backwards does not

elicit a response. Campbell points out that the work of art, the

wooden hawk, strikes some very deep chord.(2) When confronting

an mythic or archetypal work of art, it strikes some very deep

chord within us. Guerin writes that: The

relationship between myth, symbol, or archetype and mise-en-scène

has to do with a common response not only to a common experience,

but to the artistic representation of that same common experience.

The bottom line is that on a very substantive and deep level,

we all respond to common experiences because we are all human

beings. And when a common experience is represented in the theatre,

we respond similarly to the experience, even when the common experience

is not real but representation or symbol. In The Masks of God:Primitive

Mythology, Joseph Campbell tells of the phenomenon that newborn

chicks will see a hawk fly overhead and run for cover. The chicks

do not respond the same way when they see other birds. But not

only that, a wooden image of a hawk drawn overhead on a wire will

elicit the same response. The wooden hawk run backwards does not

elicit a response. Campbell points out that the work of art, the

wooden hawk, strikes some very deep chord.(2) When confronting

an mythic or archetypal work of art, it strikes some very deep

chord within us. Guerin writes that:

myth is, in the general sense, universal.

Furthermore, similar motifs or themes may be found among many

different mythologies, and certain images that recur in the

myths of peoples widely separated in time and place tend to

have a common meaning or, more accurately, tend to elicit comparable

psychological responses and to serve similar cultural functions.

Such motifs and images are called archetypes. Stated simply,

archetypes are universal symbols.

The theatrical artist/engineer does not have

to "make" these connections happen or "make"

the patron respond. They simply do. The goal here is to know what

archetypes are and how they work in order to make choices appropriate

for the production. The theatrical artist/engineer would NOT choose

a number of universal symbols in order to make the most connections,

but simply see if the engineering product falls into universal

symbol, and tap into it to help create an experience for the audience.

Guerin

offers some examples of archetypes and their symbolic meanings

with which they tend to be associated. Guerin

offers some examples of archetypes and their symbolic meanings

with which they tend to be associated.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

1. Water |

The mystery

of creation; birth-death-resurrection; purification and redemption;

fertility and growth. According to Carl Jung, water is also

the commonest symbol for the unconscious. |

| |

|

a. The sea. |

The mother of all life;

spiritual mystery and infinity; death and rebirth; timelessness

and eternity; the unconscious. |

| |

|

b. Rivers |

Death and rebirth (baptism);

the flowing of time into eternity: transitional phases of

the life cycle; incarnations of deities. |

Not all playwrights include water in their plays,

but some do. Synge's Riders to the Sea does not ask the

scene designer to include the sea as a design element. The sea

is not onstage. But the sound of the sea elicits an image of the

sea that is archetypal and appropriate for this production. The

sound of the sea and the sound of a river are two different sounds,

and two different experiences. The sound of a river would not

help the production of Riders to the Sea because people

have a common experience with sound and the response it creates.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

2. Sun |

(Fire and sky

are closely related); creative energy; law in nature; consciousness

(thinking, enlightenment, wisdom, spiritual vision); father

principle (moon and earth tend to be associated with female

or mother principle); passage of time and life. |

| |

|

a. Rising sun |

Birth; creation; enlightenment |

| |

|

b. Setting sun |

Death |

Early theatre and outdoor daylight theatre literally

connect to this archetypal image. The artistic representation,

of course, has to do with lighting.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

3. Colors |

|

| |

|

a. Red |

Blood, sacrifice, violent

passion; disorder. |

| |

|

b. Green |

growth; sensation; hope;

fertility; in negative context may be associated with death

and decay. |

| |

|

c. Blue |

Usually highly positive,

associated with truth, religious feeling, security, spiritual

purity. |

| |

|

d. Black (Darkness) |

Chaos, mystery, the unknown;

death; primal wisdom; the unconscious; evil; melancholy. |

| |

|

e. White |

Highly multivalent, signifying,

in its positive aspects, light, purity, innocence, and timelessness;

in its negative aspects, death, terror, the supernatural,

and the blinding truth of an inscrutable cosmic mystery. |

Not only painting but light offers color. Of

color, though, Guerin is writing about cultural symbol or motif

rather than universal archetypes. For instance, people of the

Egyptian culture respond to black as life, not evil or darkness,

because of their ancient association with the black life-giving

soil when the Nile floods.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

4. Circle (Sphere) |

Wholeness, unity |

| |

|

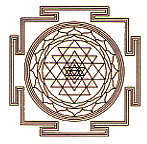

a. Mandala (a geometric

figure based upon the squaring of a circle around a unifying

center) |

The desire for spiritual

unity and psychic integration. Note that in its classic oriental

forms the mandala features the juxtaposition of the triangle,

the square, and the circle with their numerical equivalents

of three, four, and seven. |

| |

|

b. Egg (oval) |

The mystery of life and

the forces of generation. |

| |

|

c. Yin-Yang |

A Chinese symbol representing

the union of the opposite forces of the Yin (female principle,

darkness, passivity, the unconscious) and the Yang (masculine

principle, light activity, the conscious mind). |

| |

|

d. Ouroboros |

The ancient symbol of the

snake biting its own tail, signifying the eternal cycle of

life, primordial unconsciousness, the unity of opposing forces. |

Mandala

|

Yin-Yang

|

Again, Guerin writes of not universal archetypes,

but cultural symbols and motifs. A set designer would consider

these motifs.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

5. Serpent |

Snake, worm.

Symbol of energy and pure force (libido); evil, corruption,

sensuality; destruction; mystery; wisdom; the unconscious. |

Joseph Campbell wrote about just how universal

the snake is and how much people of various cultures have blamed

the snake.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

6. Numbers |

|

| |

|

a. Three |

Light; spiritual awareness

and unity; the male principle. |

| |

|

b. Four |

Associated with the circle,

life cycle, four seasons; female principle, earth, nature;

four elements (earth, air, fire, water) |

| |

|

c. Seven |

The most potent of all symbolic

numbers - signifying the union of three and four, the completion

of a cycle, perfect order. |

Numbers are associated with both shape and rhythm,

so it is often used in set design and sound design.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

7. The Archetypal Woman |

Great Mother

[Earth Mother] - the mysteries of life, death, transformation. |

| |

|

a. The Good Mother |

Positive aspects of the

Earth Mother: associated with the life principle, birth, warmth,

nourishment, protection, fertility, growth, abundance. |

| |

|

b. The Terrible Mother |

Including the negative aspects

of the Earth Mother: the witch, sorceress, siren, whore, femme

fatale - associated with sensuality, sexual orgies, fear,

danger, darkness, dismemberment, emasculation, death; the

unconscious in its terrifying aspects. |

| |

|

c. The Soul Mate |

The Sophia figure, Holy

Mother, the princess of "beautiful lady" - incarnation

of inspiration and spiritual fulfillment. |

This, of course, connects to the play itself

and depiction of characters.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

8. The Wise Old Man |

(Savior, redeemer,

guru): personification of the spiritual principle, representing

"knowledge, reflection, insight, wisdom, cleverness,

and intuition on the one hand, and on the other, moral qualities

such as goodwill and readiness to help, which make his 'spiritual'

character sufficiently plain.... Apart from his cleverness,

wisdom, and insight, the old man ... is also notable for his

moral qualities; what is more, he even tests the moral qualities

of others and makes gifts dependent on this test.... The old

man always appears when the hero is in a hopeless and desperate

situation from which only profound reflection or a lucky idea

... can extricate him. But since, for internal and external

reasons, the hero cannot accomplish this himself, the knowledge

needed to compensate the deficiency comes in the form of a

personified though, i.e., in the shape of this sagacious and

helpful old man." (C.G. Jung, The Archetypes and the

Collective Unconscious, trans. R.F.C. Hull, 2nd ed. (Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968), pp. 217 ff.). |

Again, this is in the realm of the drama.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

9. Garden |

Paradise; innocence;

unspoiled beauty (especially feminine); fertility. |

Some plays literally call for a garden scene,

like My Fair Lady. But turn this around and think in terms

of its meaning when designing and the connection could happen.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

10. Tree |

"In

its most general sense, the symbolism of the tree denotes

life of the cosmos: its consistence, growth, proliferation,

generative and regenerative processes. It stands for inexhaustible

life, and is therefore equivalent to a symbol of immortality."

(J.E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, trans. Jack

Sage (New York: Philosophical Library, 1962) p. 328.

|

| |

|

Modern video and computer games seem to use

the tree as a combination of the Wise Old Man and archetype.

| A. Images |

|

|

|

| |

11. Desert |

Spiritual aridity;

death; nihilism, hopelessness. |

Australian film tends to use the Desert archetype

to indicate a change in a character.

B. Archetypal

Motifs or Patterns |

|

|

|

| |

1. Creation |

Perhaps the

most fundamental of all archetypal motifs - virtually every

mythology is built on some account of how the Cosmos, Nature,

and Man were brought into existence by some supernatural Being

or Beings. |

And entire operas, plays, and musical compositions

have dealt with this motif.

B. Archetypal

Motifs or Patterns |

|

|

|

| |

2. Immortality |

Another fundamental

archetype, generally taking one of two basic narrative forms. |

| |

|

a. Escape from Time. |

"Return to Paradise,"

the state of perfect, timeless bliss enjoyed by man before

his tragic Fall into corruption and mortality. |

| |

|

b. Mystical submersion into

Cyclical Time. |

The theme of endless death

and regeneration - man achieves a kind of immortality by submitting

to the vast, mysterious rhythm of Nature's eternal cycle,

particularly the cycle of the seasons. |

A rather clear way to see a part of Escape from

Time is to think about the movement downward and the movement

upward. Because of a universal feeling that downward is descent

of self and upward is ascent of self, we have movement of downward

into hell or the demon ascent from the depths of hell as well

as ascent into heaven and angels descending from heaven. It would

not make sense to us if the movement related to its opposite meaning.

So we have traps in the stage floor and the deus ex machina

in ancient Greek theatre. Mystical submersion into Cyclical Time

reminds me of the ancient Egyptian drama, the Abydos Passion

Play.

B. Archetypal

Motifs or Patterns |

|

|

|

| |

3. Hero Archetypes |

Archetypes of

transformation and redemption. |

| |

|

a. The Quest |

The hero (savior, deliverer)

undertakes some long journey during which he must perform

impossible tasks, battle with monsters, solve unanswerable

riddles, and overcome insurmountable obstacles in order to

save the kingdom and perhaps marry the princess. |

| |

|

b. Initiation |

The hero undergoes a series

of excruciating ordeals in passing from ignorance and immaturity

to social and spiritual adulthood, that is, in achieving maturity

and becoming a full-fledged member of his social group. The

initiation most commonly consists of three distinct phases:

(1) separation, (2) transformation, and (3) return. Like the

quest, this is a variation of the death-and-rebirth archetype. |

| |

|

c. The Sacrificial Scapegoat |

The hero, with whom the

welfare of the tribe or nation is identified, must die to

atone for the people's sins and restore the land to fruitfulness. |

This connects to plot as well as to character

type.

- All quotes from Guerin will be from his

book: Wilfred L. Guerin, Earle Labor, Lee Morgan, and John R.

Willingham, A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature,

2nd ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1979) 154 - 162.

- Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Primitive

Mythology (New York: Viking Press, 1959) 31.

|